(1980—2025)

At the Sydney Mathematical Research Institute, we were deeply saddened to hear of the sudden death of Jérémie Guilhot. Jérémie was a valued member of the mathematical community here in Sydney. Jérémie worked at the University of Tours, France, and visited the University of Sydney on many occasions to work with his friend and collaborator, James Parkinson. Most recently, he spent a nine month sabbatical at SMRI from September 2023 to June 2024. For Jérémie and his family, this was a very fondly remembered period, spending time with friends and enjoying travelling in Australia and New Zealand. It was also a fruitful collaborative period for Jérémie professionally.

James and Jérémie first met briefly in 2009. Jérémie was concluding a 1-year postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Sydney supervised by Andrew Mathas. James was returning to Sydney from postdoctoral positions abroad to begin his permanent position. Their friendship developed when James was invited by Jérémie to give a mini course at the University of Tours and speak at a conference in the Sologne region of France in June 2016. Over the following decade, their friendship and collaboration strengthened. The two spent time together each year (with some forced breaks in the pandemic years), switching between Australia and France, and Jérémie decided to bring his family to Australia for his sabbatical in 2023/2024.

Jérémie saw the intrinsic beauty of mathematics, and in particular representation theory, and enjoyed the creative and intellectual demands of solving open problems in this area. All who knew Jérémie enjoyed his great humour, warmth, kindness, modesty, and generosity. His contribution to the field, and more generally to the mathematical community, was immense, and his loss is felt profoundly. From all of us here in Sydney, we extend our deepest sympathies to his partner Chloé, children Samuel and Colette, brother and sister Nicolas and Anne, and parents Joëlle and Jean-Noël.

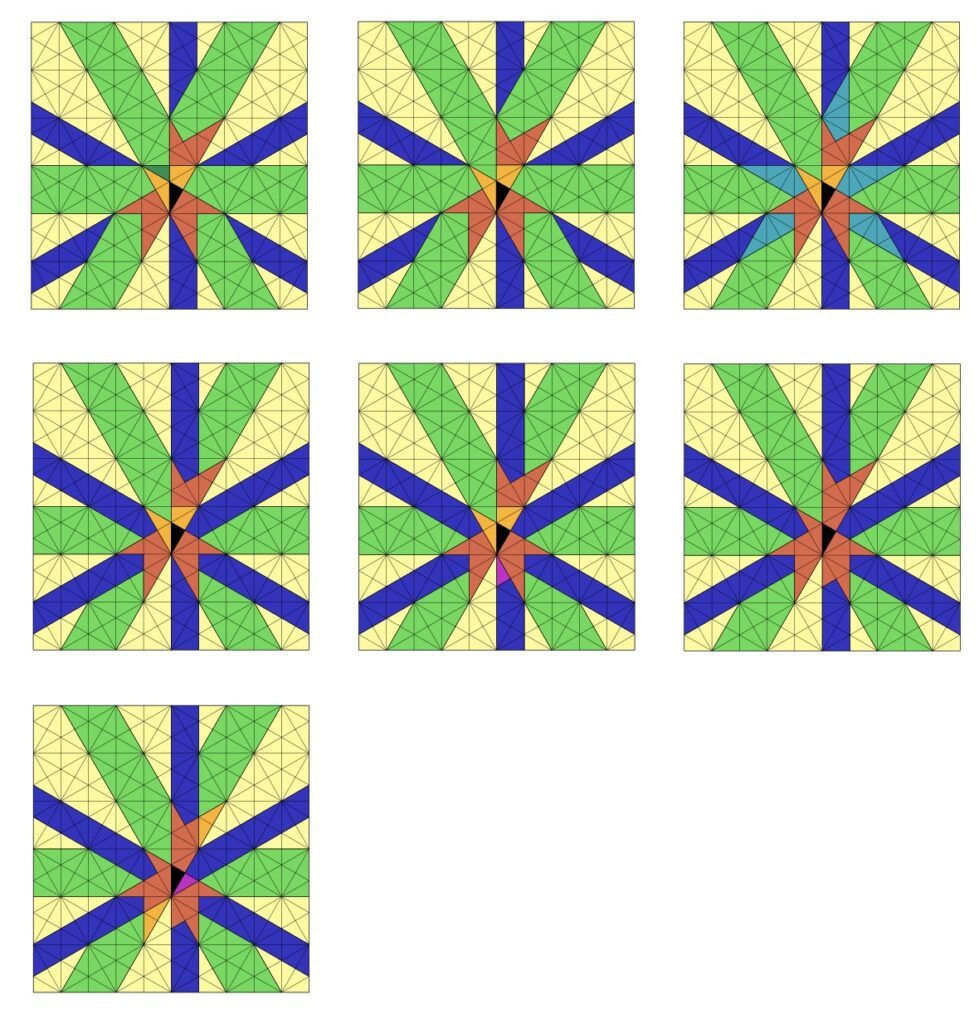

In recognition of Jérémie’s contributions to research and the mathematical community, we share some of Jérémie’s achievements, focusing primarily on his connections to Australia. The picture below was very dear to Jérémie’s heart:

We now outline the story behind this remarkable picture, and Jérémie’s collaborations in Australia that stemmed from it.

Jérémie’s research focused on several fundamental problems in representation theory, the branch of mathematics in which the modus operandi is the “representation” of complicated structures by simpler objects that are more amenable to work with. In solving a hard problem, a key step is to identify and classify the fundamental atomic building blocks of the problem. Understanding the interactions and connections between these building blocks is useful, in the same way as the periodic table is crucial to chemists and physicists as a means for organising and understanding different elements and their properties. This approach is used by those in representation theory, who take complicated abstract objects and break them down, turning them into problems that are easier to understand.

In Jérémie’s case, the abstract mathematical objects in question are called Hecke algebras, which are certain deformations of Coxeter groups. These objects are ubiquitous in mathematics as they model the fundamental notion of “reflections” in a space. A systematic approach to the representation theory of Coxeter groups and Hecke algebras has emerged over the past 45 years, following a chain of ideas initiated in a remarkable 1979 paper of David Kazhdan and George Lusztig. This theory has since become known as Kazhdan-Lusztig theory. The atomic building blocks of Kazhdan-Lusztig theory are called Kazhdan-Lustig cells. These cells give a decomposition of the Coxeter group, and for each cell there is naturally associated a representation of the Hecke algebra.

Jérémie’s primary focus centred around Kazhdan-Lusztig theory for Hecke algebras with “unequal parameters”. In this theory, the Coxeter group is deformed using multiple parameters. As these parameters vary in the parameter space one obtains multiple different decompositions of the Coxeter group into cells, producing a rich collection of representations of the Hecke algebra. The classical situation is the “equal parameter” case, where the parameter space is zero dimensional. In this special case, there is only one decomposition of the Coxeter group into cells, and deep geometric interpretations of Kazhdan-Lusztig theory led to the resolution of the long standing Kazhdan-Lusztig Positivity Conjecture by Ben Elias and Geordie Williamson in 2014. As a consequence, the equal parameter case is relatively well understood.

In contrast, for the unequal parameter case, the geometric interpretations of Kazhdan-Lusztig theory are typically not available, and the positivity properties enjoyed by the equal parameter case fail. This necessitates the development of new tools and methods to understand Kazhdan-Lusztig theory in unequal parameters. This is where Jérémie’s interests and major contributions lay.

To begin with, in his PhD Jérémie developed a form of generalised induction of Kazhdan-Lusztig cells (now known as the Guilhot Induction Process), and used it to compute the decomposition of all dimension two affine Coxeter groups into cells for all choices of parameters. At the time, these were the first non-trivial examples of infinite groups where the decomposition into cells for general unequal parameters was known. To this day, few cases are understood.

The dimension two affine Coxeter groups admitting unequal parameters have names “affine C2” and “affine G2”, and Jérémie was particularly fond of the beautiful affine G2 example. Jérémie proved that there are seven distinct decompositions into cells for affine G2 as the parameters vary in their one-dimensional parameter space. These seven decompositions are illustrated in the figure. Each connected component corresponds to a one-sided cell, and hence a representation of the Hecke algebra. The one-sided cells of the same colour combine to form a two-sided cell.

The affine G2 example was a large part of the reason why Jérémie invited James to France in 2016. Each had given talks in the Algebra Seminar at the University of Sydney in 2009 that touched on this same example (from very different perspectives). Jérémie had remembered this and perceived potential for fruitful collaboration.

This brings us to the work of Jérémie linked to his collaborations in Sydney. In 2002 George Lusztig stated an influential collection of conjectures (P1—P15) dealing with the structure of Kazhdan-Lusztig cells for Hecke algebras with unequal parameters. These conjectures encode the behaviour of the fundamental building blocks of Kazhdan-Lusztig theory and the way in which these pieces fit together. This idea forms the “periodic table” of Kazhdan-Lusztig theory. Many subsequent works in Kazhdan-Lusztig theory are conditional on the validity of P1—P15. The positivity results mentioned above imply that P1—P15 hold in the equal parameter case, but this approach fails for the unequal parameter case. Proving P1—P15 for unequal parameters therefore remains an important unsolved problem.

Early in their collaboration Jérémie and James began developing ideas towards attacking Lusztig’s Conjectures P1—P15 for affine Hecke algebras. They proved the conjectures for all dimension two examples, including the affine G2 example that Jérémie enjoyed so much. Their approach was multifaceted. Firstly, there are core algebraic ideas, building on work of Meinolf Geck, and leading to the introduction of the notion of a “balanced system of cell representations”. Secondly, there are analytic ideas, utilising Eric Opdam’s Plancherel formula for affine Hecke algebras, and leading to the introduction of the notion of an “asymptotic Plancherel formula”. Finally, there are combinatorial ideas, adapting the “path models” of Arun Ram and applying this combinatorics to study representations of affine Hecke algebras. A particular appeal of the approach, as reported by James, is the beautiful way in which these different concepts come together to work in harmony, with each idea essential to the overall complete picture. In fact, James notes that this is reflected more broadly in the way James and Jérémie’s collaboration worked —each possessing complementary expertise and intuition that seemed like magic to the other, leading to a very special collaboration and friendship.

Over the following years the pair developed their ideas further. Jointly with Eloise Little (a PhD student of James, to whom Jérémie acted as an informal co-advisor), they extended the combinatorial aspects of the work to arbitrary dimension. During Jérémie’s sabbatical in Australia the team were joined by Nathan Chapelier (a postdoctoral researcher who had also worked closely with Jérémie in Tours). Together, Jérémie, James, Eloise and Nathan worked on extending the other aspects of the project to arbitrary dimension, focusing on the so-called “affine \( A_n \) case”. This intensive period of collaboration lead the team to a new construction of Lusztig’s “asymptotic algebra” in the affine \( A_n \) case.

Jérémie’s passion and enthusiasm drove the above research, creating beautiful and lasting mathematics. His collaborators will deeply miss his insights and contributions, and will forever remember the wonderful times they had with him.

A tribute to Jérémie through the Denis Poisson Institute appears here.